For the first two years of my college, I tended to measure my faith in quantitative categories. I tallied the number of people I could convince to come to Christian events, the amount of Bible verses I could memorize, or how many quiet times I was able to squeeze in.

These practices are acts of faith to the Lord and are inherently good. The problem emerged once I began to equate my relationship with God to the output I was able to show for it.

I found pride and identity in how well I was meeting unspoken ministry expectations in college.

Then, in September of my third year, my stability was uprooted by tragedy. I lost my hero, my Dad, unexpectedly while I was here at school. I can’t really recall that week, but I remember being carried through the ER and how bright the lights were.

Coming back to school, it felt like the lights were still shining down on me. I was no longer in a place with God to continue serving in the roles I was in. This was terrifying, as I wondered who I would be without a title affirming my faith and goodness. Who am I if not the empathetic Christian? What if I don’t fully believe the scripture I read today? If God truly is all powerful and knowing, why would he let this happen?

All of the ugly, hard parts that I wanted to hide had been cast out and illuminated whether I like it or not. My deficits and fears had blinding spotlights on them and every person asked, “How can I help?”

I consider myself the luckiest to have such wonderful, caring friendships at UVA. However, that didn’t make it any easier to accept their aid. I had nothing to offer them in return and a voice in my head told me that I was needy, selfish, and inferior. I wondered if one day those people would grow weary of waiting for me to grow into a place where I had the emotional and financial capacity to give back to them.

For the remainder of the fall semester I was attempting to come to terms with my grief and depression. The latter a word I kept close to myself. I would walk around in a haze, overhearing complaints of papers, busyness, and traveling. It all felt trivial. Sometimes the sadness would drag me down to where I felt I couldn’t get up in the morning. Other times it would fade to the background and using a little bit of wit and laughter I could pass as okay.

The institutions I had built my relationship with God upon in college, failed me. There is no room for healing or grace in places that demand a full emotional and spiritual capacity from twenty year olds. I didn’t finish the race I intended to and no longer fit into the community I chose first semester. My faith was stripped down to what it was all along, a messy relationship between myself, a sinner, and a God who loves me regardless.

No one voluntarily enters a liminal space. Yet in this default posture of surrender, I was able to experience some of the greatest love. I have been provided for, comforted, and pointed back to truth in countless ways. Assurance of my belovedness came in the form of dark chocolate peanut butter cups and long drives and song suggestions. When prayers no longer left my lips with ease, they found the words I was searching for. When I felt that joy and hope were scarce, they lovingly guided me back towards abundance.

“This is the most profound spiritual truth I know: that even when we're most sure that love can't conquer all, it seems to anyway. It goes down into the rat hole with us, in the guise of our friends, and there it swells and comforts. It gives us second winds, third winds, hundredth winds. ...your spirits don't rise until you get way down. Maybe it's because this - the mud, the bottom - is where it all rises from. ...when someone enters that valley with you, that mud, it somehow saves you again.” (Anne Lamott, a queen).

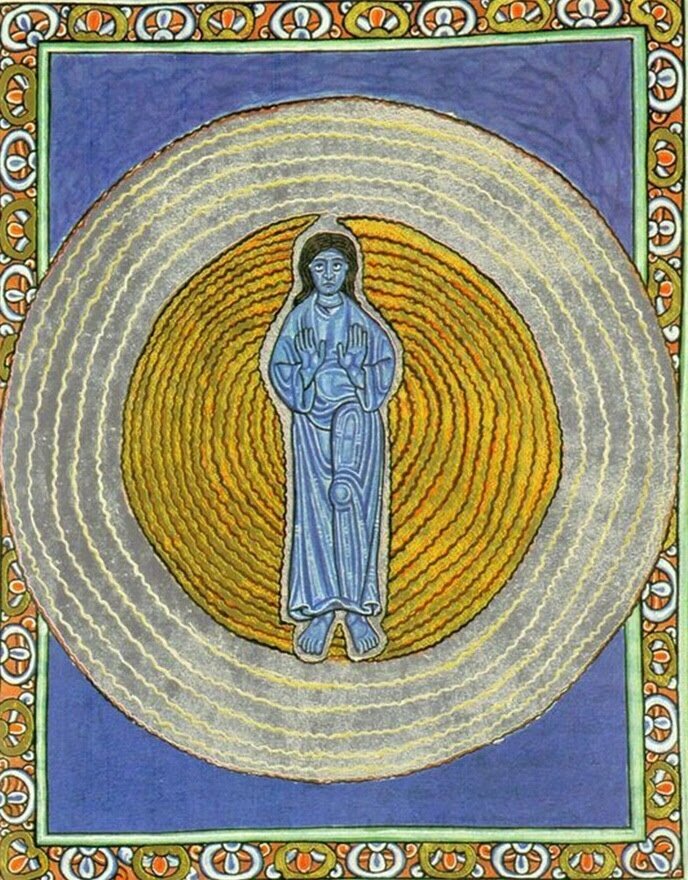

I was deep in the mud with my palms were open and high, trust that I was bitter and embarrassed about it, but radical grace found me time after time. Healing isn’t linear, it’s more like a half step forward followed by two giant leaps in the wrong freaking direction. As the seasons turned, I began to wonder if people were looking for me to transition back into my old positions of leadership. It was a pressure created internally, the pursuit of being “fine” enough to pick up where I left off.

Then I was gently reminded by those who entered the valley, that I serve a God of freedom and mercy. The Lord can handle the grief, doubt, and anger that still resurfaces now and then even if the communities and organizations I previously was apart of are not able to.

I trust that everything belongs, and that perhaps He will take the parts of my story that hurt and use it to remind someone else of how loved they are. He has the power to take grief and brokenness and turn it into a gift, an offering, to those around us. You don’t need a leadership title to do that, the title Child of God will suffice.

For the college student who is struggling, my hope is that you see your worth separate from your spiritual performance. May you instead count hard conversations, stillness, joyful banter, shared vulnerability, and even those moments of complete surrender as a reminder of your belovedness. Ah, the mystery of grace.